There is a Conservative argument that what matters is absolute levels of income and wealth. Worries about how it is distributed are for Socialists. Conservatives should just get on with growing the total size of the cake.

This view is one strand of conservatism. But there are also good Conservative reasons why this won’t do on its own. For example, Conservatives also care about social mobility up the ladder of opportunity – but the bigger the gaps between the steps in the ladder, the harder it is to move up it. There are other reasons why where you are relative to other people also matters which I hope to turn to in a future column. But there is also a link to the need for getting economic growth going.

Raising Britain’s growth rate has been a consistent theme ever since 2010. Some crises, such as Covid and Ukraine, have impacts widely spread across many advanced economies. But other challenges have hit us particularly hard, such as the impact of the financial crash on an economy with a large financial services sector and, of course, Brexit with its impact on business investment and trade.

So we are in danger of falling behind our competitors. Indeed, there has recently been a flurry of anxiety about projections showing Poland’s GDP per head could overtake ours by 2030.

Raising our growth performance is key. But it is frustratingly hard to deliver in practice. One reason is the sheer political difficulty of implementing policy proposals such as building more houses in the places where people want to live = or opening up protected parts of the economy to more competition. Why is it hard to generate the political will to do these difficult but necessary measures to raise our performance? It is possible that comparing our incomes with our neighbours provides a clue.

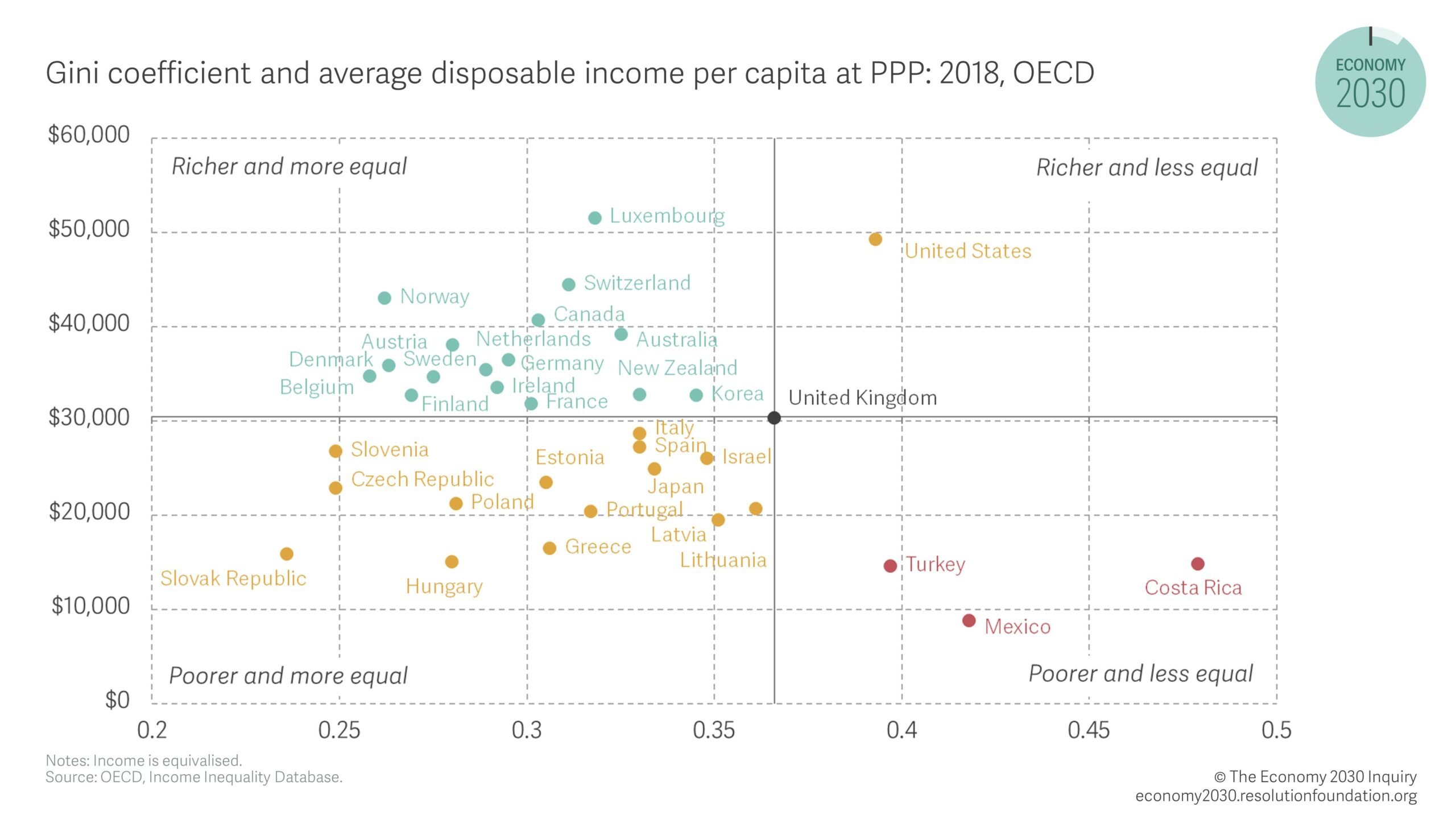

Our GDP per head is smaller than Germany or France, Sweden or the Netherlands. So boosting our economic performance is not some impossible dream. We just have to catch up with them. But there does not seem to be the political hunger to do so.

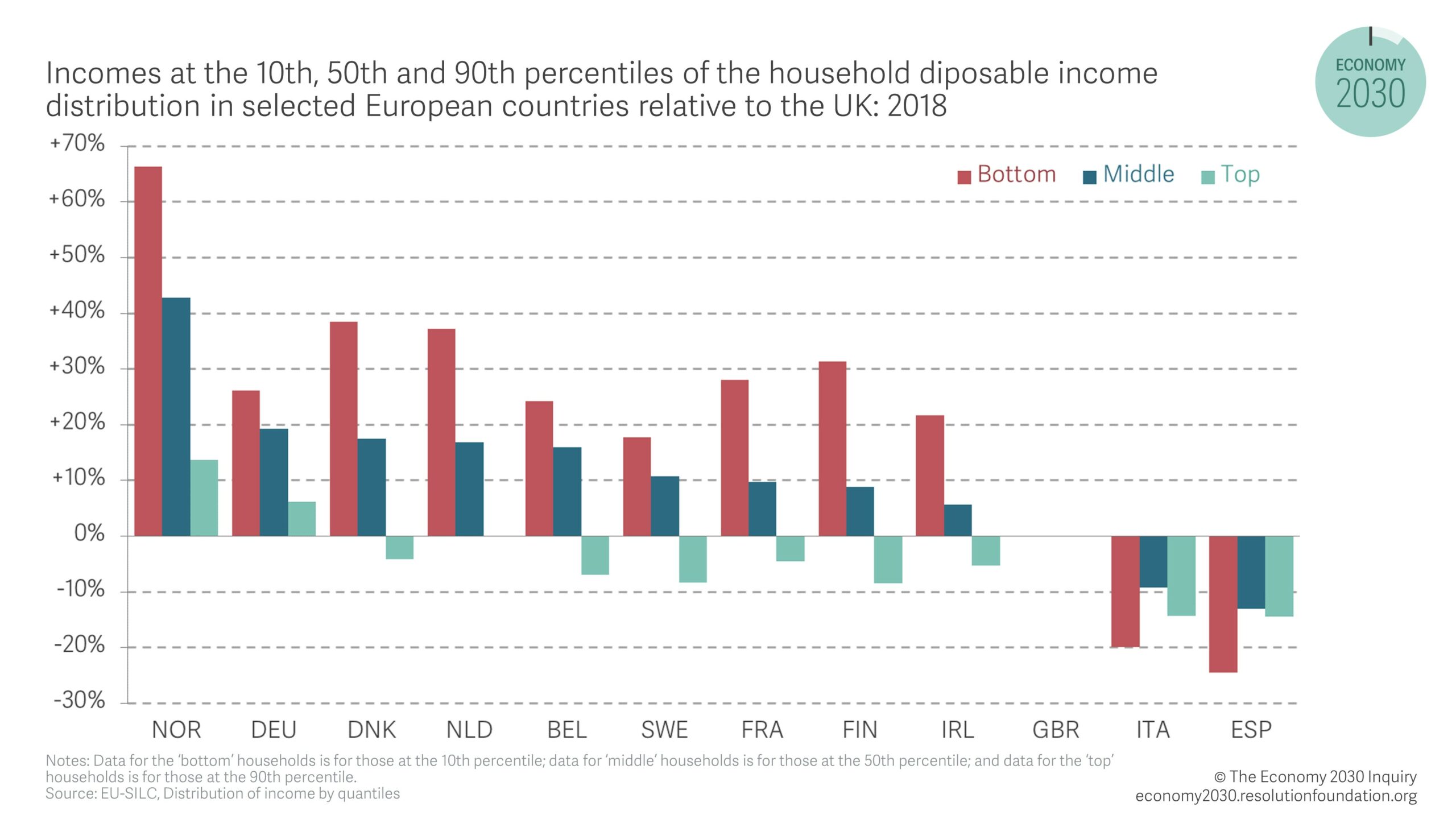

Britain’s very unusual distribution of income may help explain this. The top ten per cent of people in Britain – the leaders in business, the media, and politics – enjoy incomes broadly matching those other countries. If anything, our top ten per cent enjoy incomes slightly higher than the top ten per cent in France, and just a bit below Germany. So if a prosperous professional in Britain travels to the continent they may not feel their living standards are lower. That makes the problem of our poor economic performance all rather abstract.

But the Resolution Foundation estimates that the middle income person in Britain has an income ten per cent lower than in France or Sweden and almost twenty per cent lower than in Germany. And for the poorest ten per cent, their incomes in Britain are 20 or 30 per cent lower than in those comparator countries.

This means that we have managed to create for ourselves an economic model in which high income groups are protected from Britain’s economic under-performance. The burden of adjustment to our weak economic performance is borne by people on middle incomes or less.

Now there may be some hard-headed even if rather unpalatable economic arguments for this. People at the top are internationally mobile, so bankers in London have to earn as much as in Frankfurt or Paris. The failure to invest in basic educational and vocational skills has an impact on the wages that less skilled people can earn.

But this sounds a bit like special pleading. Imagine that every day a British business leader or lawyer or Minister dealt with their counterparts in Germany or France, they observed that their own living standards were 25 per cent lower (the gap for Britain’s poorest compared with those two countries). Would it perhaps make us a bit more willing to consider building more houses in the South East or learning a second language so we could export better?

Maybe our unusually high income gaps in Britain aren’t necessary to promote incentives and economic dynamism. Maybe we accept them as the only remaining way to protect some of us from the consequences of a poor economic national performance. And if we lost such protection, perhaps we would be as hungry for growth now as we were during the 1980s, when we really were willing to do very difficult things to get our economy performing better.

Why the distribution of income matters for growth